Homelessness in the wake of the disaster

Housing conditions in the neighborhoods affected by the Aug.4 2020 Beirut blast

A report by the Housing Monitor

I. Introduction

The Aug. 4, 2020, Beirut port blast killed 217 people, injured 7,000 others, and displaced some 300,000 people [1], causing widespread devastation and leaving no less than 1,120 buildings in need for renovation [2] , notably in the neighborhoods closest to the blast site. To date, it is estimated that only 30% of the residents of Beirut’s affected neighborhoods have actually returned to their homes. [3] .

The official response to one of the largest blasts in history came in October 2020 in the form of the “Protection of the Damaged Areas and Support of Reconstruction” law — a regulation that lacks a comprehensive and fair policy.

The law is based on an approach that is devoid of the necessary and economic social components, reducing urban planning to buildings and real estate, which always serves the investors’ interests. This approach also stresses the sanctity of individual property rights and the freedom of contract within the framework of free market economies, while ignoring the right to housing as a basic right.

What’s more, in apparent disregard to social justice, the October law denies residents the possibility of quick renovation of their damaged buildings and fails to set criteria and priorities for the renovation of the most affected neighborhoods.

Non-governmental organizations took over the renovation works in the absence of fair standards. As a consequence, evictions in the affected neighborhoods increased, most notably among renters, some of whom were prevented from repairing their houses or even receiving aid. In some cases, [landlords increased rent upon the completion of renovations], an increase which went beyond the tenants’ financial means. These practices came to reinforce partisan and sectarian clientelist networks in the affected neighborhoods, undercutting the rights components of the recovery process.

The law also provided for the extension of residential and non-residential lease contracts in the damaged buildings and properties for a period of one year, thereby protecting tenants from eviction for one year as of the issuance of the law. Yet, most residents remained unaware of their rights, and there were no official attempts to enforce the law. It was also evident that the one-year period is insufficient amid the stifling economic, financial, and social crises plaguing the country, and given that building renovation is a lengthy process, especially in the absence of fair compensation.

Amid [eviction] threats and stalled renovation processes, it appears that the residents of the affected areas are likely to face eviction, displacement, and homelessness, notably the most vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, domestic and foreign workers, refugees, women, and LGBT people. In addition to the fact that landlords usually take advantage of these groups’ vulnerability, many amongst them are either unable to land a job and thus secure a stable income, such as the elderly, refugees and women, or fear resorting to the law, such as refugees, foreign workers, and LGBT people. These groups also lack a social support network that might prevent evictions or provide them with alternative housing. This is not to mention that the absence of housing alternatives during the renovation process has constituted a major hardship for the residents, prompting many tenants to search for shelter on the outskirts of or outside the city, displacing many and emptying the affected areas from their residents.

The above-mentioned reasons did not only affect the slow renovation process in the affected area, but also created a displacement wave the extent of which remains undetermined — a wave that can only be stopped through policies and steps aimed at protecting the residents and their livelihoods. The recommendations in this regard figure at the end of the report.

This detailed report sheds light on the housing situation in the affected neighborhoods and includes reports sent by residents to the Housing Monitor, in addition to several field research conducted by Public Works Studio spanning a few years back, a few months after the blast, and nearly a year after the disaster. The multiplicity of sources and the different periods in time covered by the research allow us to deepen our understanding of the challenges facing the residents of Beirut’s neighborhoods that were affected by the port blast.

II. The reality of the affected neighborhoods and their residents

The areas affected by the port blast are largely composed of old or historical buildings inhabited by a large number of tenants. Each neighborhood has its own dynamics linked to the date of its establishment and the economic and social changes it has undergone. The destroyed area is a mix of historically marginalized neighborhoods such as Karantina, al-Khodr neighborhoods. Other neighborhoods have historically served as a haven for refugees and displaced persons, such as Karantina and Badawi. Some neighborhoods include various housing arrangements, some of which are affordable with relatively good conditions and a diverse environment where the LGBT community feels relatively safe, such as Badawi, Mar Mikhael, al-Roum, and Gemmayzeh.

These neighborhoods have also undergone major changes since 2006, with real estate speculation peaking in 2012, when the price of an apartment in Mar Mikhael jumped from $1,000 per square meter to more than $3,000 in less than five years [4] Since 2008, the local economic model of these neighborhoods started to change, shifting from a crafts-based economy and small businesses to services, with many business units transforming into bars or restaurants. Meanwhile, housing units turned into guesthouses, which displaced many residents, and exposed the remaining tenants and small landowners to the risk of losing their homes. [5] The blast came to exacerbate this unfair situation, subjecting the most vulnerable groups to the threat of eviction and permanent displacement.

Old tenants

“ MMona lives in an old building in Mar Mikhael that was already in a bad condition even before the blast. The building’s residents are either old tenants or foreign workers. Due to the serious damage inflicted on the neighborhoods following the blast, and amid the slow and murky reconstruction process, only the residents of three apartments remained in the building. Those are old tenants who repaired their homes on their own with the support of associations and have been constantly pressured to evict the premises. The landlord had notified them of the need to leave their apartments so they can be renovated, requesting them to take out all furniture because he could not be held responsible for any damage or theft. The remaining tenants refused to leave, prompting the landlord to threaten to call the police. When they insisted on staying, he threatened to go to court, without providing them with any written document or affidavit guaranteeing their return to the apartments. When they inquired about the matter with the army, they were told not to leave their houses if they did not receive a request from the municipality to do so for the renovation works.”

Eviction threats to old tenants in the affected areas is not something new. These threats are generally linked to the endeavor of demolishing old buildings and real estate development. The owners of old buildings, however, have been keen not to renovate or maintain them but to rent them out — pending reconstruction works — to vulnerable groups, through different informal housing arrangements, which would allow them to make profit at market-rate rents without any costs. The buildings that are shared by old tenants and vulnerable groups -whether refugees or displaced persons- are scattered throughout the affected neighborhoods: Burj Hammoud, Geitawi, Badawi, Karantina, Mar Mikhael, Karm al-Zaytoun and Bachoura. The buildings which once served as affordable housing pockets in the city, albeit with poor and worrying housing conditions, are today the most threatened by eviction. The real tragedy lies in the possibility of turning the affected neighborhoods into an opportunity for real estate investment.

Old owners

“ My retired mother has lived in Mar Mikhael in a six-story building for 35 years. After the blast, she stayed with me for two weeks, but she soon wanted to return to her house. For three months, she stayed there without any windows. We are still repairing the house. She was the only one to return to the building. It is empty. Immediately after the blast, they offered to buy her apartment, but she did not accept. ”

Between May and June, we conducted a quick survey of 146 forms which included: 48 new tenants, 44 old owners, 39 old tenants, 11 new owners, 3 cases of leniency in paying rent [6], and one no answer.

It should be noted that the houses of 67 persons (i.e., 46% of the respondents) are still in need of renovation, while 28% of old owners believed that they might be at risk of losing their houses.

Migrant workers

“ Issam, a Sudanese man, has been living with his wife Ada, an Ethiopian national, near al-Khodr Mosque for 11 years, in a room they rented directly from the owners. In the wake of the economic crisis, the rest of the rooms in the house became vacant because most foreign workers had left the country.

Relations with the owners began to deteriorate since that time, but things became calm when the owners moved the countryside with the outbreak of the coronavirus at the beginning of 2020, and the imposition of a nationwide lockdown. After the blast, Issam’s building was renovated through NGOs. This was when the landlords began to pressure him and his wife to vacate the premises under the pretext that they wanted to give the house to their son. Issam found out that the eviction request was illegal and confronted the landlords, who offered to move him to another apartment in the building, with defective utilities. Issam agreed, with the condition that the landlords would fix them, to which the latter replied: “You don’t even have toilets in Sudan.” In June, the owners broke into Issam’s house and prevented him from using the newly renovated kitchen, and forbade associations from entering the building, and tenants from visiting each other. ”

Migrant workers were in fact particularly affected by the blast. Based on a meeting for the affected neighborhoods’ residents held at the Migrant Community Center of the Anti-Racism Movement, seven out of 10 migrant workers were evicted due to damages to their homes and the owner’s reluctance in carrying out renovation works. Two remained in their houses in Ashrafieh and Geitawi, both of which need renovation, while no association took the initiative so far to repair the broken windows and doors. One owner of an apartment in Dora did the necessary repairs but increased the rent. The blast caused widespread damages in areas as far as Furn al-Chebbak, Burj Hammoud, Dora, Karm al-Zaytoun, which did receive aid from relief organizations that focused more on zones which are closer to the blast site. Two residents managed to stay in the same neighborhood, while the other five had to move to farther-away areas such as Byblos, Hazmieh, Ain al-Rummaneh, and Sin el-Fil. Half of the meeting’s attendees lost their jobs because of the blast. Those who managed to land a new job are now living far from their workplace and have a hard time securing the cost of transportation.

Refugees

“ I live in a small building divided into two apartments. A relative of the owner lives in the opposite flat. When someone came to inspect the building, the owner said there was no one living in our apartment, although my family and I have been living there since 2007, which the owner had to admit when all the neighbors testified to this. In any case, I no longer have any documents to prove anything. They were all destroyed. ”

According to residents’ reports, Karantina is one of the neighborhoods whose residents were most subjected to eviction attempts in the aftermath of the blast. The Housing Monitor received 46 reports from Karantina residents, nine of whom were evicted from their houses. According to an NRC study [7] run on a sample of housing units, Syrians in Karantina constitute 50% of the residents. Those were subjected to discrimination by their landlords; by the army upon the distribution of compensation; and by some aid associations. Most of the organizations were focused on providing aid to the neighborhood as it was the most marginalized amongst the neighborhoods damaged by the blast. Some landlords, however, seized the opportunity to renovate their houses that were dilapidated even before the blast, in a bid to rent them out at a higher price, especially for non-Lebanese tenants, taking advantage of the latters’ legally fragile situation. During a meeting attended by 22 Syrian residents fromKarantina, stories were told about forced evictions carried out by owners who used their influence in the area.

LGBTQ community

“ I live in Camp Hajin, at the end of Armenia Street. My a small apartment is one of five others in the same building. After the blast, new tenants from different nationalities replaced the old ones. I was the only tenant who stayed. The owner did not repair anything. An organization inspected the building from the outside but did not renovate the apartments. The window we repaired was leaking when it started to rain. The army visited us once to give us two bundles of bread. The discrimination we witnessed between the different neighborhoods is surprising. Of course, I would like to stay in the neighborhood. It is comfortable and significant for the LGBTQ community. ”

During a meeting for LGBTQ residents held at the Helem Association, it was found that attendees did not leave their homes in the aftermath of the blast, despite the poor housing conditions. Their houses are still not fully renovated, and others face new housing conditions. One person has been renting a bed in a three-room house for the past three years. Two people live in each room. They used to contribute LL600,000 each to pay the rent. After the blast, the apartment’s owner added a new bed in each room, overcrowding the place. It is difficult for members of the LGBTQ to move away from these neighborhoods, where they find some acceptance and safety.

Some social groups such as old residents, especially the elderly, migrant workers, refugees, and LGBTQ people, are clearly facing flagrant and ongoing violations of their housing rights. As evidenced by the stories above, reflecting these vulnerable group’s daily suffering whether in keeping or defending their houses, many residents are often left on their own in the face of attempts to turn their homes into investment opportunities, which rob them of the possibility of improving their economic and social lives, pushing them towards the city’s peripheries. Meanwhile, those who manage to stay in the center are facing extremely difficult conditions.

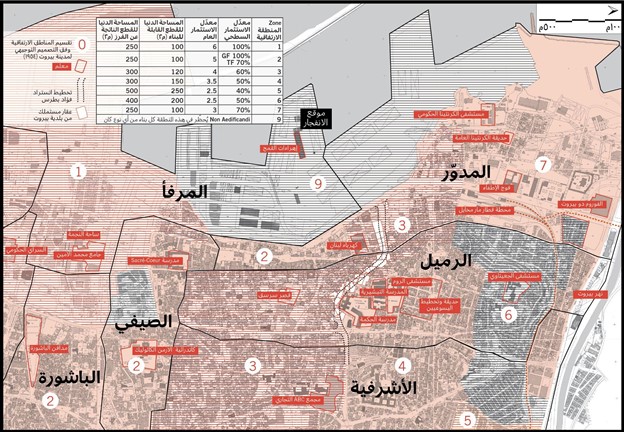

III. What does the geographical distribution of reports tell us?

The Housing Monitor followed up on 127 reports from areas affected by the blast between September 2020 and June 2021. The reports included more than 474 individuals, including 177 children, 18 elderly people and eight people with special needs. It should be noted that 58% of the reports were made by migrants and refugees of different nationalities, and the rest by Lebanese. Most of the calls we received were from women who live alone, single mothers, or women looking after their families. We published a separate report on this issue. [8]

We also received 41 reports from adjacent areas in Karm al-Zaytoun, Burj Hammod, al-Bashoura, Zukak el-Blat, and Nabaa, as well as eight reports from farther away areas, also affected by the blast, notably al-Bushrieh, al-Mazraa, Dbayeh, al-Ghubeiry, and Ras Beirut.

|

Classification of affected areas |

Areas |

Total number of reports |

Total reports from residents before the blast |

|

Neighborhoods that are not subject to prohibition of land ownership transfers and other land transactions as per law 194/2020

|

Rmeil, Saifi, Mdawwar, the Port |

78 |

74 |

|

Districts and neighborhoods that are not subject to prohibition of land ownership transfers and other land transactions 194/2020 |

Ashrafiyeh, Burj Hammud, al-Bashoura, Zukak el-Blat, Nabaa |

41 |

35 |

|

People affected by the blast from farther away areas |

Al-Bushrieh, al-Mazraa, Dbayeh, al-Ghubeiry, Ras Beirut. |

8 |

6 |

Many people affected by the blast reported being evicted or threatened with evictions and other abusive practices. We also received reports from people inquiring about legal issues in relation with their rent contracts, as well as the reconstruction and compensation processes. In our analysis, we used an expanded definition of “affected areas,” and enlarged the concept of “damage” to include harms not taken into account by the law, namely physical injuries causing permanent incapacity for work or having caused the victim to lose their job or source of livelihood, as well as the death of a breadwinner in a household. These damages have exacerbated housing vulnerabilities and increased housing costs.

The Karantina neighborhood, located in al-Mdawwar real estate area, had the largest share of reports (41 cases), namely al-Khodr neighborhood in which a large portion of Syrian nationals live. Reports from Syrian refugees constituted 22 cases, i.e., 50% of the total cases, followed by Burj Hammoud with 18 cases, and Nabaa with 13 cases, most of which filed by workers and migrants or refugee families, representing 85% of the total reports in the two neighborhoods. We received 13 reports from six old tenants and five refugees or migrants in Mar Mikhael. 83% of the total number of reports were filed by new tenants.

97% of the reports were made by residents, compared to two cases by a shop owner, one case by a restaurant and hostel, and another one by a factory. The reports included various housing arrangements, a large number of which are informal. 72% of the reported cases were made by tenants of entire apartments, 25% varied between rooms rented directly from the owner through informal divisions of the housing unit, or shared housing in an entire apartment rented by individuals or families sharing the rent, or makeshift tin units on building roofs, or shops in which owners have added sleeping accommodations, in addition to an abandoned house and a janitor’s room.

|

Reported housing arrangements |

|

|

Entire apartments |

92 |

|

Rooms rented directly from landlord |

16 |

|

Co-renting entire apartments |

7 |

|

Makeshift units on roofs |

4 |

|

Shops with sleeping accommodations |

2 |

|

Abandoned house |

1 |

|

Janitor’s house |

1 |

Despite the blast’s serious impact on the entire population, its consequences on housing security reproduced and exacerbated the already existing vulnerabilities, in terms of the social and economic situation, and the geographical distribution of the vulnerable communities who were most affected and most likely to lose their homes in the aftermath of the tragedy.

IV. Types of residential violations

We were able to monitor the emergence of new patterns of practices threatening housing security in the aftermath of the blast, which were directly linked to the consequences of destruction, rehabilitation and compensation. These violations were documented in their various forms.

In what follows, we present details of the forms of housing rights violation experienced by those affected by the blast, as well as the housing vulnerabilities that resulted from the subsequent initiatives on the part of associations, as well as the authorities’ fragmented procedures, and the violations of the “extension of lease contracts” clause stipulated in Law 194/2020.

Eviction and eviction threats

Suffering from several vulnerabilities, the residents of affected areas were also subjected to different violations. Forty-four cases of evictions were monitored out of the 127 reported cases. Also, eight people among those who reported their cases were evicted after the blast and are at risk of being evicted again. We also received 91 reports of eviction threats.

The Housing Monitor received 115 reports from people who have been residing in the affected neighborhoods since before Aug. 4, including 35 cases that reported eviction, 27 were within the districts subject to prohibition of land ownership transfers and other land transactions as per law 194/2020, which was ostensibly put forth to protect the affected areas and their resident from real estate speculation.

Out of the 44 reported evictions, 37 were final evictions, 7 temporary evictions, pending the return to the rented apartment buildings. Repeated cases of evictions from districts that are subject to prohibition of land ownership transfers and other land transactions were also documented. These were 8 cases and were part of the final 37 permanent evictions.

A protection clause that does not protect the tenants

Eviction threats come in many disguises. Sometimes, the landlords increase the rent upon the completion of renovations paid for by NGOs. They also try to confiscate the allocated aid before tenants can access it. In some cases, the landlords refuse to carry out renovations or allow the tenants to do so themselves. At other times, they try to end lease contracts or refuse to renew them.

The cases received by the Housing Monitor reflect how poorly tenants are protected amidst the economic and health crisis hitting Lebanon. The main reasons behind the evictions of the affected population was the rent, with 38% of the cases (14 cases) reporting it. Nine cases reported that they were no longer able to secure the rent. In four reported cases, the tenants could no longer afford paying the rent when the landlord decided to increase it. In one reported case, the landlord requested that rent be paid in “fresh” dollars and not according to the official exchange rate, pegged at LL1500. These cases were found in the neighborhoods of Karantina (4 cases), Burj Hammoud and Nabaa (4 cases). There were also six other cases scattered in the affected neighborhoods, one of which was in Sabra where a family was previously evicted from Karantina after the blast. Five cases reported an increase or change in the rent value according to non-official exchange rates in districts subject to prohibition of land ownership transfers and other land transactions as per law no. 194, which also extended the contracts (with an extension of the original contract conditions) up to an additional year, for all affected buildings without taking into account their geographical location.

It was striking that this clause was not implemented by the local authorities, while most of the tenants were not aware of their rights. In one case, the landlord changed the rent in exchange for allowing the tenant, who had vacated the house for renovation works, to return to the leased property.

In two other cases to be added to the 14 reported cases, tenants were prevented from returning to their homes in Karantina after a temporary eviction in the aftermath of the blast, unless they paid rents accrued from previous months.

Twenty-seven of the evictions were classified as evictions in violation of Law 194/2020, because the tenants were forced to vacate the premises not as a result of grievous reasons such as a demolished house in the aftermath of the blast but rather as a result of pressures ignoring the clause on extending rents which were usually accompanied by arbitrary practices that the tenants were unable to address through legal means — an option they didn’t have most of the time.

High risk of arbitrary practices and inadequate housing conditions

Eviction threats were not limited to verbal threats.Physical violence and forced evictions were carried out, exacerbating the suffering of the residents who are still trying to survive the trauma of the horrific blast. This is not to mention the fact that many of both the old and new residents of the affected neighborhoods continue to live in poor living conditions, in destroyed houses. These neighborhoods became the main destination of the most socially and economically vulnerable groups because of the presence ofNGOs providing relief efforts and social protection for the LGBTQ community.

Moreover, the landlords’ control over access to aid was a reason to evict Syrian families from Karantina. Three of these families had reported this to the Housing Monitor. These cases were also associated with racial discrimination and arbitrary practices such as threats of physical assault and forced evictions over ration boxes supplied by the associations to the tenants. Sometimes, the landlords and their families would evict the tenants to move in themselves in a bid to benefit from the aid and compensation instead of the previous tenants. In one reported case, the tenant chose to leave the house because of the blast trauma. In 15 other cases, however, the tenants reported violations and arbitrary practices such as water and electricity cut off, threats of forced eviction and forcible entry to the house, seizure of property and identification papers, as well as verbal abuse and insults.

Lack of housing alternatives during renovations

The state has left the most vulnerable groups subject to homelessness and forced them to bear the burden of securing housing alternatives in a context which lacks the social policies resulting in decent and affordable housing.

|

Difficulty to find a housing alternative |

9 |

First, it should be noted that a number of cases found it difficult to secure alternative housing due to several reasons, most notably the residents’ inability to afford the rent. Amid the high cost of living, rent has become a greater burden on the tenants. This is in addition to the fact that several of those who reported their cases lost their jobs after the blast or suffered bodily injuries preventing them from resuming their work. Also, rent increased in the midst of the economic crisis and after the renovations carried out either by the associations or the landlord. Most of the residents who were evicted from their homes moved to live outside Beirut (18 cases), while some decided to settle on the city’s peripheries in neighborhoods such as Furn al-Chebbak, Burj Hammoud, Sabra and Chatila, Jdeideh, Antelias. Other residents moved to farther away areas, such as the Bekaa Valley.

Sixteen cases reported returning to live in the city, nine of which went back to the same neighborhood, and seven to another neighborhood. Social relations and living conditions played a major role in these residents’ decisions to relocate. The five cases that moved to live in the Bekaa, for instance, chose areas where they have relatives living in camps for the displaced, which helped them in their move. As for the nine cases that remained in the same neighborhood, five of them were Syrian families in Karantina, many of whom stressed the need to remain in the same neighborhood despite the difficulty of finding a new house. This was caused by their established social networks upon which they rely to manage their day-to-day affairs, not to mention the proximity to their work, as most of the Syrian residents of Karantina work at the port and its facilities.

New housing vulnerabilities after the evictions

|

Homelessness |

2 |

|

Repeated evictions |

4 |

|

Temporary housing |

4 |

New housing vulnerabilities emerged after the evictions. Some of the evacuees had a hard time finding housing alternatives because of the repeated evictions and homelessness status. According to four reported cases, tenants were evicted more than once after the blast, with three cases unable to afford paying the rent, and one case of a dispute with the landlord as the tenants received assistance from an association. All these cases are related to Syrian families in Karantina. In two other cases, the families had to stay in the street for several days before finding a housing alternative. Four cases stayed with their relatives’ or friends or moved from one house to another because they were unable to find another housing alternative.

Absence of a clear and comprehensive renovation approach

The cases of temporary relocation that were caused by the blast risk to turn into permanent displacement due to the absence of compensation and clear mechanisms for restoration. According to a survey conducted by Public Works Studio in a residential neighborhood between Armenia Street and Khazenin Street in October 2020, 42% of the apartments were permanently vacated, compared to 58% classified as temporarily vacated until renovation is complete. Many tenants left permanently before the end of their written or verbal contract because they were unable to bear the costs of renovations, or because of psychological trauma, or they were not in a position to wait for the completion of renovation works. Many were unwilling to make preliminary repairs because the legal framework does not protect tenants while allowing landlords to increase rents or simply refuse to renew the lease. There were seven cases of temporary evictions, all of which related to renovation works. Three cases reported delays in repairs on the part of organizations, and the tenants’ inability to carry out major repairs themselves —these cases were documented one month or more after the blast.

According to the other four cases, the houses were still under renovation, with two cases reporting slow renovation works and the lack of communication with the landlord. According to the last two cases, tenants were under threat of permanent eviction by the owners.

In light of the renovation processes that are being carried out through the General Directorate of Antiquities, repairing heritage buildings is not based on an occupancy study that takes into consideration the residents’ social and economic backgrounds, and therefore does not prioritize the return of the most affected and most vulnerable groups.

Some houses were damaged to the point where they became uninhabitable (13 cases or 35% of cases), which was another reason for evictions. All these evictions took place immediately after the blast or within a few days. Seven cases were reported in Karantina, three in Mar Mikhael, as a result of colossal damages affecting the housing unit, or causing the destruction of old and structurally unsafe houses. In four cases, the tenants had to vacate the premises after the landlords refused to carry out the necessary renovations at the tenants’ request. In one of these cases, the landlord refused to carry out the repairs in a bid to pressure the tenant to leave, in order for him to move into the house, especially since the tenant did not have the financial means to carry out the renovations himself. It should be noted that these cases were in relations with families, nine of which were Syrian. Another case is added to the 13 cases, whereby a tenant was prevented from returning to their apartment that they vacated as a result of damages. This was, however, a scheme by the intermediary company which manages the apartment buildings on behalf of owners. The tenant had already paid their rent for the months of August and September upfront. The company was evading refunding them or securing an adequate housing alternative.

In such scenarios, some landlords take advantage of the law which grants them the exclusive right to obtain a renovation license for damaged buildings, which undermines the rights of tenants or stockholders in small land plots to renovate their homes or places of work.

Moving to the post-blast affected areas

|

Moving to affected areas after the blastMoving to affected areas after the blast |

14 |

|

Moving to apartment buildings damaged by the blast |

5 |

It is interesting to know that some residents moved to live in the affected areas after the blast. We have documented 14 cases of relocation, five cases of which reported moving to damaged and unrenovated apartment buildings.

In one case, the tenant and the landlord negotiated to deduct the cost of repairs from the rent. In the other four cases, however, the tenants waited for the associations to carry out renovations.

The deteriorating structural and housing conditions resulting from the blast have served as an excuse for the exploitative housing conditions imposed on tenants in search for affordable housing in Beirut’s affected neighborhoods.

There have been five reported cases of tenants who moved to damaged apartment buildings, four cases of which concerned Syrian tenants in Karantina and Mar Mikhael, and another tenant of the LGBTQ community. Previously suffering from homelessness, she had been facing hardships in finding an apartment to rent with landlords being acceptant of her gender identity and lifestyle..

The remaining 11 reported cases were in relation to foreign workers and migrant families who moved to affected neighborhoods and were scattered between Karantina, Burj Hammoud and Nabaa. NGOs and aid organizations were keen on excluding people living in the post-blast affected areas from their aid programs, although those have also been deeply impacted.

The Christian Endowment (Waqf) also participated in the eviction in its properties

Properties owned by the Christian Endowment are scattered across the affected areas, some of which have been vacated and others are in the course of being vacated. Large swathes of lands in Karantina are either owned by the Christian Endowment or the municipality, which makes the neighborhood a fertile land for affordable housing. The religious institutions, however, disavowed their social responsibility in terms of securing housing alternatives in the aftermath of the blast. Instead, two religious institutions were keen on evicting two tenants, one of them of an old man renting in Karm al-Zaytoun. The other tenant was also an old man with his wife, who lived in a small factory in Karantina. They were forced out of their houses.

V.A new pattern of housing rights violations

The housing crisis in Lebanon did not start and will not end with the Beirut port blast. In recent decades, land policies and housing legislation have not met the actual needs of the population. Housing continues to be quite expensive for the majority of citizens, and marginalized groups continue to bear the brunt of this. The report shows how older people, refugees, women, people disabilities, migrant workers, and LGBT people are the most exposed to evictions and housing insecurity.

A closer look at the affected neighborhoods shows that the prices of lands on heritage sites and areas have increased and have become subject to fierce real estate speculation. These areas were home to residents of all walks of lives and different social backgrounds who have struggled with eviction for many years. Available data and studies also show existing dispute regarding land ownerships, disputes over inheritance and joint ownership, and lack of ownership documents among other issues that existed before the blast and exacerbated with the blast, mostly affecting the most vulnerable groups.

The blast, however, created a new two-pronged dimension: The first bringing back to mind the reconstruction process, which indicates quick money from renovation works and real estate operations. According to an old female resident in Karantina, she had serious concerns that the damage caused by the blast would prompt her landlord to sell his buildings, which will entail the eviction, herself included. The Housing Monitor also documented 22 cases in relation with 16 buildings the owners of which expressed a possible aspiration for real-estate development or increasing the rent. Most of the reported cases (15 out of 22) were scattered between the areas of Karantina, Mar Mikhael and Gemmayze. The landlord was never clear with the tenants on their intention about developing the property. But we were able to monitor development works carried out on the property. In the same vein, we documented 19 reports in one building where the landlord was pressuring tenants to vacate the premises. We also received five reports from another old building in Karantina, where the landlord owns two other buildings at least in the same area and have voiced his desire to demolish them on many occasions. There were also five reports from four different buildings, the owner of which was either an investor or a real estate company pressuring the tenants to evict.

|

Observed Arbitrary practices related to real estate investment |

|

|

Attempts to use renovation works as a pretext to evict tenants |

3 |

|

Owner of several building that evicted some of the tenants, most of whom were old tenants. All residents face different pressures. |

6 |

|

Endowment property: evicting a tenant who used to pay a nominal amount for rent. Endowment institutions made several eviction threats in cases of low profit rents. |

1 |

|

Refusal to carry out renovation works and raising rent after the blast as a means of pressure to urge tenants to evict the premises |

1 |

|

The landlord is either an investor or a real estate company pressuring tenants to evict |

5 |

|

The landlord carried out repairs in the damaged building and is renting out for a higher price |

1 |

|

After being renovated by an association, the landlord has been pressuring the current tenants to evict so he can rent the building out for a higher price |

2 |

|

Eviction by Endowment owning a number of empty houses in in the surrounding area, in a neighborhood which has been witnessing a pattern of real estate development |

1 |

|

The attempt to use temporary eviction for purposes of renovation, as a tool to question the old tenant’s right to the rented apartment, store, etc. |

1 |

On another level, real estate speculation and post-blast pressure are closely related to the post-destruction renovation process. In reality, structural damage to old buildings has long been used as an excuse to demolish the buildings to make way for new profitable projects and/or to evict tenants. More than a year after the Beirut port blast, the current housing landscape can be defined as follows:

- The absence of any integrated plan to renovate the damaged houses and reconstruct dilapidated buildings.

- The subcontracting of all renovation works by public institutions and official competent authorities to NGOs and the private sector which proved their inability to complete all the required work.

- The lack of coordination and clear referral mechanisms for renovation cases, including the cooperation between residents and aid and relief providers , as well as rampant clientelism؛

- Lack of compensation for the people, while aid and cash assistance distributed by the Lebanese Army were unfair and biased.

In the same vein, the renovation works were a cause for housing anxiety undermining the social and economic recovery of the affected areas. We documented 43 cases where tenants were negatively impacted by renovation works, including 23 cases reporting problems resulting from repairs, and 20 other cases in which no renovation works took place.

Refugees and migrants represented 55% of those affected by the consequence of the renovation process. Twenty cases were registered in this effect: 14 in Karantina, and six in Burj Hammoud. These two areas are considered the last to include affordable housing in the heart of or adjacent to the most important economic facilities in the city.

Furthermore, the most major problems that were reported include raising the rent upon renovation works completion (7 cases), slow or unsteady renovation works (4 cases), preventing tenants from returning to their premises upon the completion of repairs (3 cases).

Some practices were racist, targeting foreign, refugee or migrant families, as well as attempts to confiscate the aid meant for tenants. The landlords’ refusal to carry out renovation works, and the delay or absence of association intervention were two main factors that made repair works impossible (13 and 12 cases, respectively). One of the cases we followed closely on was that of Em Nazih Café and Beirut Urban Gardens, which were severely damaged and where the renters were not allowed to carry out renovation works.

|

22 reports in relation with renovation |

||

|

Poor renovation process |

Total reports |

Total related practices |

|

Landlord argues that the building is no longer safe as a pretext for eviction |

6 |

2 |

|

Partial renovation (not enough) |

2 |

|

|

Slow/faltering renovation process |

4 |

|

|

Antiquity license problem |

1 |

|

|

Lack of funding/financial ability to carry out repairs |

2 |

|

|

Delay in associations response |

2 |

|

|

Result/after renovation |

Total reports |

Total related practices |

|

Increased rent |

16 |

7 |

|

Preventing tenants from returning to the premises |

7 |

|

|

Landlords want to take back the leased apartment due to familial reasons |

2 |

|

|

20 reports in relation with problems due to lack of renovation |

||

|

Lack of renovation |

Total reports |

Total related practices |

|

Landlord refusal/prevention of renovation works |

20 |

13 |

|

Association refusal of carrying out renovation |

2 |

|

|

Delay or no show-up on part of associations |

12 |

|

Ultimately, housing protection in the areas affected by the blast and at any point in the post-destruction period, must be an integral part of a comprehensive and integrated path to renovate and rebuild the areas according to clear goals taking into account justice, livelihood opportunities, and sustainable urban recovery.

VI . Recommendations

More than half of Beirut’s residents are renters. [9] While they suffer from dire economic conditions, costly rents, barely making ends meet and almost failing to secure daily services, they have been faced with the horrific forms of exploitation since the blast, in a bid to expel them from their own houses, increase rents, and terminate contracts.

To protect the population from the risk of homelessness and from being cut off from their social and economic environment, the state is required to intervene to address the inadequate legal framework on housing rights, starting with the need to draw up a national housing plan that translates Lebanon’s international commitments into governmental policies protecting and guaranteeing this right for all, working on developing a housing sector, activating the public institutions’ role in providing affordable and stable housing. The plan must include the following:

- Regulating the rental market, setting fair rates according to clear criteria, exclusively using the national currency for rents.

- Establishing eviction conditions in accordance with international law standards.

- Monitoring and reducing vacancy in residential and non-residential units, by imposing progressive taxes primarily on real estate investors, and launching housing programs which increase available, convenient, and inclusive housing stock, while supporting small owners who live off of rent.

- Encouraging housing cooperatives by providing tax exemptions and the possibility of financing or lending for the construction of housing, in a bid to allow low income communities to join their efforts and gain access to affordable housing.

- Activating monitoring mechanisms to observe inclusive and adequate housing standards and eliminate housing discrimination.

- Establishing housing projects in line with the urban, social and cultural environment that could also benefit the poorest segments of the population.

As for the short term, and in order to respond quickly to the needs of the population affected by the blast, and speed up renovation efforts, we suggest the following:

- Amending Article 5 of Law 194/2020 to extend lease contract throughout the renovation period instead of just one year of renewal. Determining the mechanism to apply this article, in terms of informing mayors, police stations and local authorities.

- Adopting a zero-eviction policy and activating the role of public and local authorities in securing adequate alternative housing, when necessary, close to the necessary facilities.

- Integrating abandoned buildings and vacant apartments into alternative housing programs for the tenants awaiting the completion of renovation works or those who were evicted as a result of an increase in rent.

- Facilitating the procedure to obtain a renovation license by passing an exception allowing all residents, owners and renters to proceed with the renovation process. This is in addition to removing all administrative obstacles and adopting more flexible and less expensive standards for the renovation of heritage buildings.

- Forming a coordination committee for reconstruction which would include all the representatives of the affected communities, especially the most vulnerable groups.

- Approving the lists of damages, the compensation mechanism and a timetable for its distribution.

- Ending the privilege of Solidere and other real estate companies which allows them to invest in real estate in the affected areas.